The Albigensian Heresy by Christopher (Rusty) Tunnard

The Albigensian Heresy, Extracts from a 1985 guide book to the Midi Canal and the Languedoc

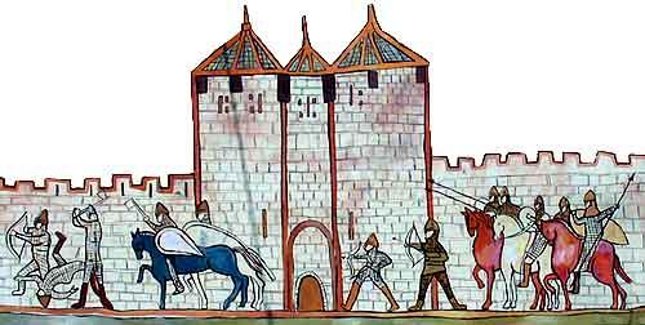

Every Western schoolchild is taught about the Crusades and the valiant Crusaders, Richard the Lion-Hearted and his fellows, who sallied forth from medieval Europe to rid the Holy Land of the infidel, protected by the banner of the church and the blessings and promises of eternal salvation by the Pope. From a more secular (and practical) point of view; the Crusades were a way for the leaders of that time to gain tremendous riches and territorial influence. It was no problem for them to amass large armies by promising the peasantry a share of the rewards.

Such was the case in one of the most vicious but least chronicled Crusades, that of the combined forces of the king of France and the Pope against the practices of a belief known as Catharism, or the Albigensian heresy (after Albi, one of its centres). This Crusade occurred in the early thirteenth century Originally named Manichaeism after its third-century Persian founder, Mani, the heresy was carried along the trade routes to eastern Europe and eventually to southern France. It is a dualist philosophy, which follows from the belief that man and the physical world were created by Satan in revenge for his expulsion from heaven and that only spiritual beliefs and God himself are good. Thus, it denies procreation, Christ's existence, and almost every other basic precept of the Catholic church. The most devout practitioners were called Cathares (catharos meaning "clean" in Greek). These men lived ascetic lives, eating nothing that was the result of a sexual union (except fish; perhaps they were not aware of how fish reproduce) and avoiding all human contact. Less demanding memberships were available for those who wished to lead more normal lives.

In order to understand how this extraordinary belief could have flourished in southern France at that time, it is necessary to look at the power and political structures of the area After Charlemagne's death, France was divided up among local feudal lords, leaving the northern section under the control of the king and much of the Languedoc in the hands of the counts of Toulouse and Foix and the viscounts of Carcassonne and Béziers. Of these, the Counts Raymond of Toulouse had the most influence because of their vast holdings, many of which were rewards (rather ironically as it turned out) for doing battle in the Holy Land. Theirs was a tolerant reign. when the heresy began to spread during the tenth and eleventh centuries, they allowed it to do so for two reasons: First, in their desire to keep their vassals content and to avoid any uprisings, they supported the heresy; second, the Catholic church was beginning to gain wealth and power by selling indulgences and establishing powerful bishoprics, and the counts saw no reason to share their wealth and benefits with local bishops or the Pope. By the beginning of the thirteenth century the heresy had spread throughout the Languedoc, carried by zealous missionaries who preached to public gatherings (a new technique at the time).

At the same time, Pope Innocent III began looking for ways to restore the power of the papacy, which had been severely diminished by the loss

of Jerusalem and the abandonment of the spiritual mandate for temporal riches, to wit the sacking of Constantinople in 1204 by Venice and its allies. He saw a perfect opportunity to

restore his spiritual ascendancy by converting the heretics of southern France, and in1205 he dispatched the man who was to become St. Dominic to do just that. It soon became clear,

however; that conventional missionary methods were not enough to combat the firm entrenchment of the heresy. After his legate, Pierre de Castelnau,

was murdered in St. Gilles in 1208, the Pope preached a Crusade against the counts of Toulouse and all who followed the Albigensian heresy.

Innocent

III found a willing ally in Philippe-Auguste, the king of France, who himself saw a golden opportunity to bring the south of the country

into his domain. In 1209 the combined armies of France and the Pope marched on the Languedoc, besieging and conquering Béziers and Carcassonne in short order. Then,

because of the expiration of the forty-day conscription period prevalent during this era (the quarantaine), the regular soldiers and their leaders returned home, leaving the rest of the

fighting to the fanatic Simon de Montfort (a member of the Leicestershire family in England) and his followers (mostly from Normandy).

The remainder of the military campaign was an endless series of sieges, culminating in the capture of Toulouse and the Treaty of Meaux in 1229, which put an end to the hostilities and ceded much of the Languedoc to the king of France and his allies.

However, the heresy was not expunged by any means, and the Pope (by this time Gregory IX) launched the first Inquisition, that infamous system of

tribunals that dispensed summary and swift justice against all non-believers, to put an end to the Cathares. Many heretics sought refuge in remote castles in the Pyrenees,

but these, too, were besieged and conquered; by 1260, the last of the heretic strongholds had fallen.

The most significant legacy of this short episode in the history of France

is that it was the first of many religious conflicts which were to embroil Europe in war for several hundred years. The heretics and their bravery have been, perhaps, overly romanticized by

modern writers. However, a small number of followers still adhere to some of the tenets of the faith, and several cults of mysticism, loosely based on the Cathare tradition, have appeared

in recent years.

from The Canal du Midi and the Languedoc - a Sightseeing Guide - By Rusty Tunnard (deceased).moc.lanacidim@ytsur